Tags

Antisemitism, Charlottesville, Holocaust, Roland Barthes, Trump, Women's March London, World War 2

Footage of Hitler reflected in a glass display, IWM 2016. Photo: Jaime Ashworth.

As a blogger with a background in Holocaust Studies, Godwin’s Law (sometimes the authoritative-sounding reductio ad Hitlerum) is a constant source of controversy. As originally formulated by Mike Godwin in 1990, it runs:

As an online discussion grows longer, the probability of a comparison involving Hitler approaches 1.

While I appreciate that as a Holocaust scholar and educator I’m a bit of a niche market, this commonplace of Twitter put-downs raises some problems for me.

First, from my perspective, there’s the problem that since I’ve invested an awful lot of time and effort in trying to understand the Holocaust and the Third Reich, the likelihood of my seeing resemblances that others don’t is slightly higher than average. At a recent session run by Robert Eaglestone of Royal Holloway on the cultural impact of the Holocaust, he asked the group to identify resonances between the Third Reich and the Harry Potter books. He said there were eight. I got to ten at a rate that slightly alarmed my ‘pair’ – though this may have been the fact that a grown man is so familiar with the differences between Purebloods, Half-bloods and Muggle-borns. (I will obviously refrain from repeating what Malfoy calls Hermione in Chamber of Secrets.)

The point here, though, is that neither I nor Eaglestone is suggesting that one has to read Harry Potter either as a neo-Nazi code or a passionate anti fascist parable. We’re suggesting that ideas and images from the Third Reich, World War II and the Holocaust have woven themselves deep into our subconscious, both individual and collective. Eaglestone’s most recent work takes as its starting-point the words of the late Nobel laureate and Auschwitz survivor Imre Kertesz, who in his 2002 Nobel Prize speech spoke of the “broken voice that has dominated European art for decades”.

My work, as I have described before, is concerned with the ways the Holocaust has become a mythology – in the sense used by Roland Barthes of “a language in which one speaks” of other things. In this sense, resonances and echoes are what I look for. Sometimes this is educationally effective, as when pointing out the “magical thinking” in the term “brainwashing” which many students use to talk about attitudes to persecution amongst “ordinary” Germans. Some of the problems faced by those who attempted to try and apportion responsibility for the Nazi era can be seen in the comment by Barty Crouch Junior (while disguised as Alastor ‘Mad-Eye’ Moody) in Goblet of Fire:

Scores of witches and wizards have claimed that they only did You-Know-Who’s bidding under the influence of the Imperius Curse. But here’s the rub: how do we sort out the liars?

To be clear: I wouldn’t suggest anyone quoted this in their History exams, or that the world created by J.K. Rowling is simply a vehicle for allegory. There are, however, some obvious ways in which the Harry Potter books are (in Eva Hoffman’s phrase) after such knowledge. Rowling’s magical hierarchy is, consciously or otherwise, very similar to the race laws of the Third Reich. That such pseudo-mathematical pigeonholing of human beings is not confined to that era (look up the word octaroon) also means, though, that we have to ask why these atrocities have caught our imaginations, both cultural and individual, so powerfully.

But that doesn’t mean we can’t draw attention to the resemblances where they occur. Not least because it allows us to critique more problematic examples of Holocaust discourse, such as John Boyne’s The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas, which is most intelligible as a sentimentalised garbling of Holocaust representations rather than a response to the history itself.

In addition to the presence of Holocaust consciousness in fiction, there is a long history of invoking the Holocaust to describe the present in ways that are problematic. Peter Novick, in The Holocaust and American Life (1999), wrote of the ways in which the Holocaust had been instrumentalised by different causes: right, left and centre. Michael Marrus (in his 2016 Lessons of the Holocaust) has also questioned whether “universal lessons” are easily drawn, arguing that “lesson seeking often misshapes what we know about the event itself in order to fit particular causes and objectives [with] frequent unreliable basis in historical evidence and their unmistakable invitation to avoid nuance.”

A quick google of ‘abortion holocaust’ (a target of Novick’s) provides a case in point. Survivors of the Abortion Holocaust attempts to mobilise support to restrict the rights of women through a twisted appeal to high school social studies. Its assertion that “Any person born after January 22, 1973 is a survivor of the abortion holocaust” is as mendacious as any Holocaust denial website but in its cadences and vocabulary mimics the rhetoric of Holocaust remembrance just as its website attempts to mimic graffiti. Their Twitter feed also provides examples of Holocaust discourse, as well as sub-Trumpian attacks on “fake news” and Hillary Clinton: dire warnings of what would happen (in their view) if a woman’s right to choose stretched as far as holding high political office.

In instances like this, Godwin’s Law is not just a useful reminder that comparison can be emotive rather than accurate or helpful. It’s actually an alarm for dishonesty.

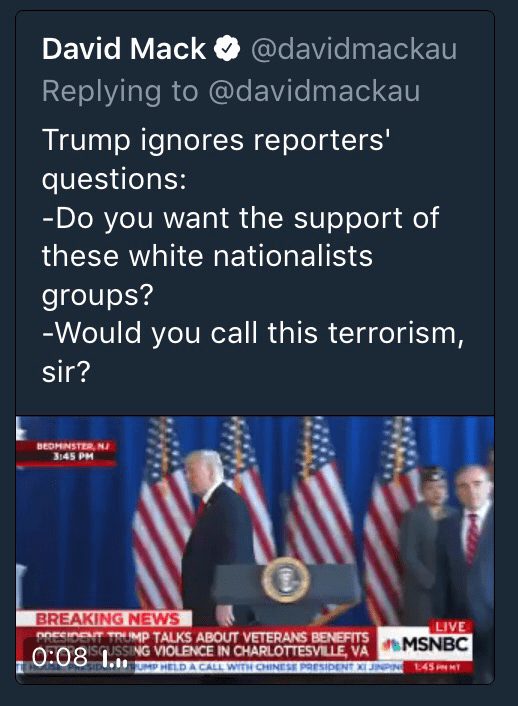

But this doesn’t address the real problem of whether a particular group can be termed “Nazi” or “fascist”. It does, though, bring into focus that Holocaust discourse and imagery is employed in many ways that stretch the facts. I became concerned that I had broken Godwin’s Law last week in referring to the events in Charlottesville as a “Neo-Nazi” demonstration. Was I ramping up the rhetoric without sufficient basis?

In the case of Charlottesville it seems that there were a variety of extremists present. Its very title, “Unite the Right”, indicates that it was intended to bring together disparate factions. The cause around which they came together, the statue of Robert E. Lee, was an American one. Images suggest the Confederate flag was as popular as any – though unambiguously Nazi imagery was certainly also present.

This diversity of extremity has made the search for an umbrella term rather difficult, not helped by the White House’s struggle to formulate a response that reaches (let alone goes beyond) equivocation. Not Nazis or fascists or white supremacists, they insist, but the “Alt-Right”.

(Only yesterday, He-who-should-not-be-president has attacked the removal of these monuments as “the history and culture of our great country” being “ripped apart”. Rather appropriately, his stance on this could be a line dance: one step forward and two steps back.)

But what does that mean? Does “Alt-Right” denote something new and different or is it just a marketing exercise; a veneer of respectability over old nastiness?

Part of the problem is that defining what MacGregor Knox termed the “fascist minimum” is not straightforward, since far-right movements are much more locally specific than others. If as Roger Griffin suggests, “palingenetic ultra-nationalism” (the extreme nationalism of national rebirth) is a good working definition, then umbrella terms will always be difficult to find. An Italian Fascist was different from a German Nazi, and both were different from a Spanish Falangist. Insistence on local difference and superiority will mean that “fascist” is likely to be an adjective ascribed by others rather than a name chosen by the group or individual in question. Though I would also point to images from Charlottesville which suggest there were plenty of people apparently flaunting their fascist or Nazi beliefs.

On these grounds, I’m happy to describe “Alt-Right” as an American fascism: insisting on a vision of racial superiority and the restoration of a mythical past (former “greatness”) through violence while positing “degeneracy” (of others, of course) as the root of all that is wrong: thanks to Rebecka Klette for highlighting this element.

That these views find expression amongst those who feel economically dispossessed and disconnected, and/or threatened by progress in social relations, merely lends weight to the comparison. An apparent obsession with a particular version of muscular, military, anti-intellectual masculinity lends more. The first target of Nazi book-burning was the Institute for Sexual Science run by Dr Magnus Hirschfeld: fear of other sexualities was a major part of the Nazi profile. Finally, one should remember that links between these examples go both ways: eugenics and biological racism were essential parts of the American view on race and German “racial science” acknowledged the debt.

But does this still make the label “neo-Nazi” overly reductive and unhelpful? Perhaps, but here’s the rub. If “Alt-Right” is the label these people prefer, then I choose to find something else, something less palatable in Peoria. If “neo-Nazi” causes the biggest shrieks of indignation and the most absurd verbal gymnastics to refute it, then I’ll use that, on the grounds that it clearly touches a nerve. In this instance, I’m with Mike Godwin, who tweeted the other day: “Referencing the Nazis when talking about racist white nationalists does not raise a particularly difficult taxonomic problem.”

Sign at the Womens’ March London, January 2017. Photo: Jaime Ashworth.

Historical comparison is never exact and always requires a light touch: the sign above from the London Women’s March does the job with admirable clarity and a touch of humour. Situations arise in unique combinations and contexts, the actors similarly unique. But as long as we recognise that, we can also do what humans do best: use lessons from the past to guide future action.

To address the title of this piece: it should be remembered that the boy who cried wolf was eventually faced with a wolf. I suspect that we may have come to that point: whether all of those who gathered in Charlottesville last week were programmatic Nazis is beside the point. That their agenda and actions were not immediately and roundly called out by those in power is the problem. Keep shouting “Nazi”: even Mike Godwin is ok with that.

Firstly, the problem

Firstly, the problem

I stopped for a while and considered what he had said. Was I becoming obsessed? One of those people who relies on third-hand summaries of second-hand accounts of made-up comments? Or could something else be going on? I retorted and await a response.

I stopped for a while and considered what he had said. Was I becoming obsessed? One of those people who relies on third-hand summaries of second-hand accounts of made-up comments? Or could something else be going on? I retorted and await a response.