Tags

AJR, Child Refugees, Commemoration, Gathering the Voices, Generation2Generation, Holocaust, Holocaust Education, Holocaust memory, Holocaust Second Generation, Intergenerational trauma, Memorialisation, Memory Studies, NHEG, Postmemory, Refugees, representation

I’ve spent the last two days at a conference organised by the Association of Jewish Refugees (AJR), exploring the challenges of generational relationships to the events of the Nazi era. I’ve spent a lot of time in the last couple of years working with Generation2Generation, which trains speakers from the second and third generations to present their family stories, and the experience has been extremely thought-provoking. I was hoping for a space in which I would be able to think three-dimensionally about the work I do with G2g and how that relates to the broader scope of Holocaust Studies and especially Holocaust Education. In an intriguing hybrid format (Day 1 online and Day 2 both online and in person at Chelsea Football Club), it did not disappoint.

Firstly, it made clear why it is so important to work with subsequent generations. AJR Chief Executive Michael Newman opened Day 2 by noting that the organisation has recently reached the point where the numbers of “first generation” members is matched by second- and third-generations. The conference was a part of a shift in orientation to ensure that the organisation remained relevant to all of its membership.

A number of organisations are either making that shift or have been established to meet that need. G2g is joined by the Manchester-based Northern Holocaust Education Group (NHEG) and the Scottish organisation Gathering the Voices. The ‘45 Aid Society, established around the postwar child refugees known as ‘The Boys’ has also developed its generational offering with a fascinating website describing these remarkable life stories: as their video emphasised, in many cases produced by their descendants. The presentations by representatives made clear how busy all these bodies are. The post-survivor era is not here yet – though there is broad acceptance that it is nearing – but when it comes they can rest assured that their descendants (and allies) will carry their legacy forward bravely.

What that will look like, however, is very much in flux – and should remain so. Rabbi Jonathan Wittenberg spoke movingly of how he realised that his upbringing was an unusual one: “I thought I grew up in North London. I didn’t: I grew up in a German-Jewish enclave in North London.” He spoke of his wife’s hilarity when they first met that he couldn’t name the Beatles, so used was he to the sophisticated, cultured milieu of the family dinner table. But he underlined that this led him to look outward, remembering the Biblical admonition “No sojourner shall you oppress, for you know the sojourner’s heart, since you were sojourners in the land of Egypt” (Exodus 23: 9) In a more mundane, but possibly even more powerful moment, Hannah Goldstone of NHEG spoke of taking her daughter shopping to buy sanitary supplies for refugees. Why are we doing this, her daughter asked? “Because we know refugees. Because we’re from refugees” was the answer.

Listening to many different stories of exile and rescue over the two days, I was struck by the way that the legacy is part of British society in unpredictable ways. Many of the Kindertransport passengers, like the mother and uncle of G2g speaker Tim Locke, did not identify as Jews – in fact his mother rejected that label as an imposition of the Nuremberg Laws. The legacy of the Holocaust thus stretches well beyond what is sometimes called “the Jewish world”: to the leafiest parts of the Home Counties, even. It is therefore vital to look to the next challenge, the relationship of the past to our present and future. In conversation with Stephen Smith, Elisha Wiesel noted that his father, Elie Wiesel, viewed the genocide in Rwanda as equal in importance and uniqueness to the Holocaust – or any other genocide.

Uniqueness is a problematic word in the context of Holocaust Studies. It implies a “preferential” view of the Holocaust that seems to jockey for a spotlight. But there is no necessary contradiction: the Holocaust had its unique elements – its singularity – just as Rwanda did (just as Yugoslavia did, just as…, just as…) but it is in its belonging to a class of events – genocides – which makes it of universal relevance. To look outside and meet the eyes of other groups recovering from (or experiencing) atrocity is a route to healing, and also a way to ensure the continuing relevance of this history to the world.

Though for many the past will never be exactly history, but who they are. The American storyteller Lisa Lipkin took listeners on an amazing inner journey through her family’s Holocaust legacy. There were a lot of good jokes, but my abiding impression was of the sadness in her eyes, and the catch in her voice as she described encountering her aunt’s blue kerchief from Auschwitz in a USHMM warehouse. I wondered if, in the many sessions she has run, that gaze has been truly held and returned. It’s a look I see at the back of the eyes of many of the second-generation, and why (I suspect) so many of them are driven to talk, and teach, and try to express that pain that is both theirs and not theirs. The search is for language above all: this may be “postmemory”, but it is not post-pain. And pain, as Jean Amery famously wrote, cannot be communicated, only inflicted.

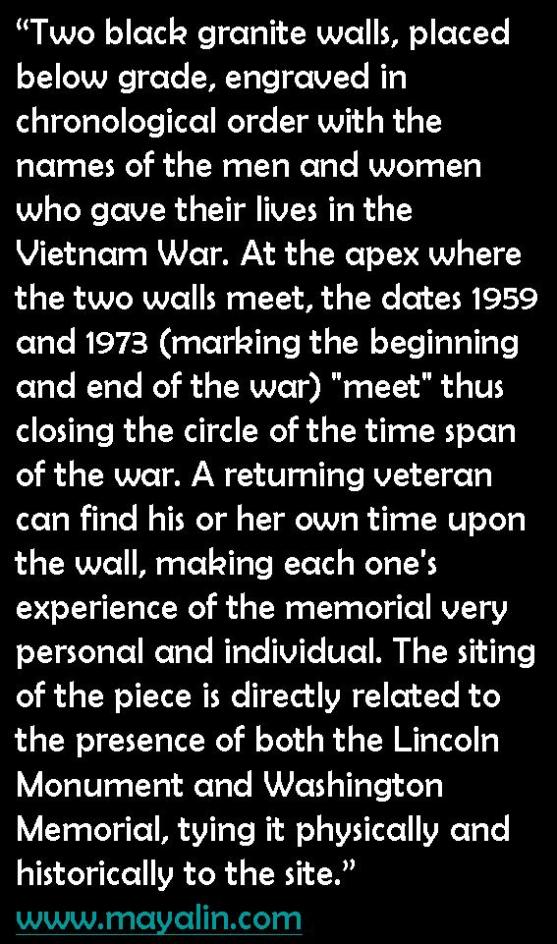

The issue of language dominated a discussion between Bea Lewkowicz of the AJR’s Refugee Voices project and two second-generation. All the voices (some recorded) noted the way that the language of their families was a crucial marker. The daughter of Valerie Klimt, in a recorded interview, noted that German constituted a “secret code” for the family – which prompted a ripple of knowing giggles from the audience. But equally Ed Skrein, a Game of Thrones actor, was shown saying that the Holocaust was always present in his family (his grandparents came from Vienna), but that “They would never speak of it in personal terms.” I reflected that perhaps the belief that the Holocaust is beyond representation – or Unspeakable, as an Imperial War Museum exhibition once described it – comes partly from the strained silence in many families: unable to speak of it, but unable as a result to speak of little else.

A session with the sociologist and journalist Anne Karpf crystallised these thoughts. She described the challenges of writing and revisiting her memoir The War After, she spoke of how she resisted the task of writing initially: “Why do I have to do it?” she says she sobbed to her partner. And then she questioned the way writing the book “sort of froze me…into being the child of Holocaust survivors.” But then she spoke of how the idea of intersectionality helped her see the past as one component of a kaleidoscopic range of identities. One definition, perhaps, but not necessarily defining.

But it was her thoughts on Holocaust memory that really struck home. She raised the idea (following Dominick LaCapra) of “archival fetishism” and the sacralisation of the Holocaust – even her unease at the “second-generation” label. She suggested that there needs to be a clearer distinction between the remembered self and the remembering self, a sharper choice between the overwhelming of memory and the rootlessness of forgetting. “I want,” she said proudly but also slightly plaintively, “to retain the right to contest my previous narrative.”

At this, I remembered the value of in-person conferences: the chance to sit quietly, and listen, and think among the like-minded and curious. How do we balance the demands of remembering for the future while forgetting for the present? The answer, I suggest, lies in language. I often return to the concept of mythology as framed by Roland Barthes (the language in which we speak of other things) as a central part of my academic life and approach. What if we saw “The Holocaust” as a language? As anyone who has learned a language knows, vocabulary and grammar act to both enable and circumscribe expression, and to transmit knowledge and values – the ingredients of what might be termed “usable” remembering. And as the people around me demonstrated, languages can be moved between: we do not always have to “speak Holocaust”, any more than we have to speak French, or German, or Italian, or Polish, however useful or integral to our selves they may be at moments. We always have a choice to rewrite – or re-speak – ourselves.

The poet Michael Rosen spoke in the morning to AJR’s Alex Maws about his journey to find and attempt to understand his family’s past – to fill in the strange gap where his great-uncles in particular should have been. As someone whose early literacy was heavily influenced by his poems, it was a treat just to be in the room: the chance to have books signed was not one I was going to miss. Looking through his volume of poems about migration, On the Move, I was struck by the importance of language: the Yiddish words his parents use are a recurring theme. “Mum can speak two languages/and sometimes mixes them up” begins one poem. And in the introduction, he notes the power of poetry – the music of language – as “a way of thinking [which gives me a space to talk about things that are personal to me, but it also lets me leave things hanging in the air… To ask questions without giving too-neat answers.” What better mode of remembrance could there be?

Links to the various organisations mentioned are included in the text: any and all them are appreciative of support. The two-line quotation in the final paragraph is from the poem “Two Languages” in Michael Rosen, On the Move: Poems about Migration (Walker Books, 2020. RRP £9.99). The lines from Exodus are from Robert Alter, The Five Books of Moses: A Translation with Commentary (W.W. Norton & Company, 2004).