Tags

Artificial Intelligence, Auschwitz, Holocaust, Holocaust Denial, Holocaust memory, Holocaust Photography, Never Again, NotoAI

Images In Spite of All, or Images in Spite of the Facts?

Above: Mendel Grossman (1913-1945) takes a self-portrait. He chronicled the Lodz Ghetto until his deportation to Auschwitz; he is reported to have died on a death march. Many of the negatives of his images were held in Israel and lost in the 1967 war. (Image from Wikipedia)

The ubiquity of the Holocaust in popular culture has always had costs. The saccharine American version of Anne Frank in the 1959 film; and the blockbuster Schindler’s List both received criticism for their simplification of a complex reality. In an age in which we are forced to surrender more and more of our creative and intellectual autonomy to AI, they are a starting-point for reflection.

Anne was a complicated, contradictory personality whose development into a woman was (among other things) chronicled in what her father determined would be The Diary of a Young Girl. Her reflections on adolescence, religion, sexuality and identity were excised, and her control of our understanding of what happened in the Secret Annexe has made it difficult to actually think through the challenges for all concerned in her predicament: being in close confinement under threat of death with a teenager must have been a challenge. (The BBC adaptation of the diary, starring Ellie Kendrick as Anne, does a particularly good job of bringing out this aspect.) The 1959 film turned Anne (ironically played by an actress in her twenties just six years Anne’s junior) into a simpering and rather pathetic figure, with (as many have observed) her Jewishness pushed into the background.

In 1993, Steven Spielberg turned an untrustworthy and feckless chancer (who did a lot of good) into a tragic hero in opposition to a bottomlessly corrupt and evil opposite: the commandant of KL Plaszow, Amon Goeth, played by Ralph Fiennes. It prompted widespread calls for Holocaust education and coincided with the opening of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. But many people have pointed out the film’s flaws. Fundamentally, it is still a Spielberg movie, with a clear moral arc (focused on a man who initially saw Jews as a resource to be exploited) and a redemptive ending. It popularised the Talmudic adage that “He who saves a life, it is as if he saved the world entire”, but the film is actually quite uncurious about what those lives meant. “The list is good; the list is life”, but how was it made? And who was not included? The arresting image of Schindler addressing the factory makes clear the relative status of rescuer and rescued.

Liam Neeson as Oskar Schindler announces the forthcoming liberation in Spielberg’s 1993 film (IMDB)

The 1990s also saw instrumental use of the Holocaust as a rhetorical weapon for unlikely causes. Perhaps most egregiously, the claim by the NRA that the Jews should have had guns to defend themselves. This not only reduced the tragedy of European Jewry to the Gunfight at the OK Corral, it also implied that gun owners were a persecuted minority on a par with the victims of genocide. The consequences of such disingenous faux-victimhood is visible in every news item from the contemporary United States.

But at least these claims were rooted in an agreement about what was real. In the last few days, my social media has been subjected to a slew of AI-generated “images of the Holocaust” by the “90s History” feed: not my choice, but a result of the algorithms’ ability to present the virtual world without discussion.

These images are disturbing. Based on stories which even I (with thirty years of reading on the subject) can’t easily identify as fact or fiction. The accompanying images take elements of the Holocaust and build a parallel universe of images which could not have been.

Another 90s blockbuster, The Matrix, is useful to consider here. Amid the hysterical, cartoonish violence, a serious point is raised. In a simulation, how can we know what, if anything, is real? The movie says the trick is to know “that there is no spoon”: thus, Neo (Keanu Reeves) can make the world behave as he sees fit.

The philosophical depth of The Matrix is a matter for debate. But at one point a glimpse is given of Jean Baudrillard’s Simulacra and Simulation (1981; English 1983). Baudrillard argued that simulacra – copies for which there are no originals – were a burgeoning feature of the postmodern condition. Art Spiegelman’s MAUS, which reproduces his father’s Auschwitz testimony in graphic novel form, with Jews ”played” by mice, poses something of this challenge. But so too does Schindler’s List, in that it is arguably more faithful to Thomas Keneally’s novelisation of the story than to the facts themselves. But in each case, we can find solid ground under our feet. Plaszow existed, so did Goeth. Władek Spiegelman existed, as did Art’s brother Rysio, murdered by the person hiding him. It is essential to remember that these were real.

But the woman holding a child as she walks through a simulated “Arbeit Macht Frei” gate? The woman delivering a baby in what appears to be a wooden barracks allegedly in the Lodz Ghetto? The women proceeding through “Auschwitz” in identical woollen overcoats rather than the rags such prisoners were given? The nonexistent memorial tablet in a part of the Auschwitz camp that does not exist?

It might be argued that these are uses of technology to fill in gaps. But the historical record is evidence and gaps, in the same way that music is sound and silence. Both are needed: one for aesthetic purposes and the other for epistemological and ontological reasons. A Holocaust in which everything was saved, all is known, is much less of a Holocaust. It is the implied gap in the vast Book of Names held at Auschwitz – for which two million names will never be known – that provides the impact.

FAKES

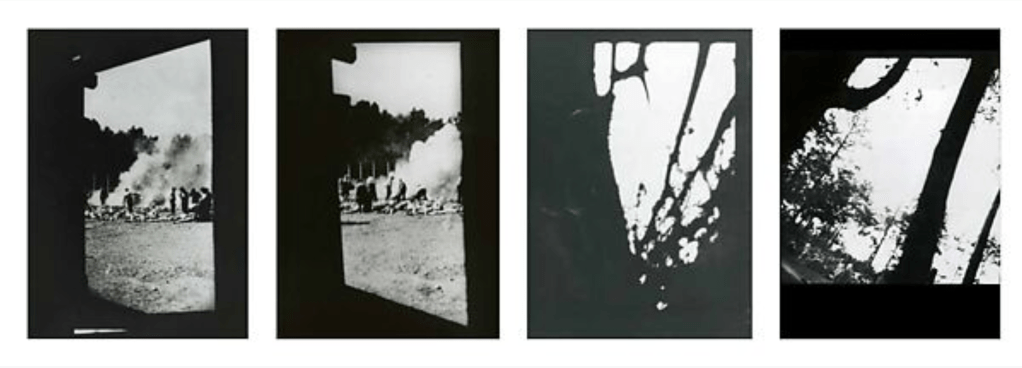

The smooth glossy surfaces of AI are infinitely easier than the real thing. The gritty, hastily taken “images in spite of all” (Didi Hubermann) taken by the Sonderkommando in summer 1944, as prototype gas chambers and burning pits had to be used to cope with the endless stream of deportations, are blurry, badly framed, at odd angles. But this is testimony to the reality of the situation: taken with a camera stolen from luggage brought by the victims, fearful of discovery. The author John D’Agata and fact-checker Jim Fingal begin their fascinating The Lifespan of a Fact with two epigrams from Lao Tze: “True words are not beautiful” and “Beautiful words are not true.” The flaw in the lens, the smudge in the record, the gap in the tape: this is the texture of evidence.

Above: the photographs taken by the Sonderkommando at Auschwitz II-Birkenau, Summer 1944 (Metropolitan Museum of Art digital copy)

It is possible that critics of this view might call me a Luddite. I wrote in 2017 of the risks I believed were posed by the efforts to create interactive holograms of survivors. I feared what they might be able to say in the future, uncanny purveyors of algorithmic “wisdom“. In the age of deepfakes I’m only surprised (and dismayed) that the world has changed so fast. But this confusion will only favour those who continue to deny, distort and denigrate the memory of the Holocaust: against such duplicitous and mendacious fakery, the best historian will flounder. We do not need to make their jobs easier in the quest for clicks: to do so is to cheapen the event we sigh wistfully over before scrolling onward.

And what to do? The director of Shoah, Claude Lanzmann, once said that if he encountered film of the gas chambers he would be compelled to destroy it. While I am unsure whether I could watch such a film, my instinct as a historian is that preservation is generally preferable. As a record of the insanities of the 2020s, these images may be valuable in the future. But these images are also, in my opinion, the historical equivalent of littering. So for now, I suggest two established technologies are most useful: the delete key, and the off switch.

For the follow up piece on reactions: click here.

Note: I’m now registered with Buy Me a Coffee: if you found this post useful or interesting, please consider sending me a small amount to help me do more. Thank you! https://coff.ee/jaimeashworth