Posters of those kidnapped on 7 October 2023 on a postbox in Golders Green, North London, November 2023. Photo: Jaime Ashworth.

I never thought that I would have to rebut the idea that the Nazis weren’t that bad, at least not in the pages of the Jewish Chronicle. But the article by Douglas Murray published on 9 November did exactly that, and generated considerable attention. While many Holocaust historians and educators have categorically rejected Murray’s argument, it has, as is the way of social media, also attracted a lot of praise, including from within the Jewish community. But then, if the first casualty of war is truth, then nuance is surely the second.

Murray’s piece in the JC was followed by an article by Andrew Roberts on the Free Beacon website last Friday. Its argument was substantially similar to that of Murray, and was predictably promoted by Murray as “a very important piece by a leading British historian and peer”. I’m not sure what relevance the peerage has, but presumably Murray thought it would appeal to his audience.

Before we go any further, I need to make clear that I am in no way minimising or relativising the atrocities of 7 October 2023. It was carnage. Those responsible need to feel the consequences, and of course, the hostages need to come home. All of them, as quickly as possible.

But we also need to recognise that an event does not have to be the Holocaust to be awful. There is an argument that the effort to make Hamas into greater villains than the Nazis in fact cheapens the actual facts of 7 October, as though they were not horrible enough. The dying on that day, and the suffering after, is awful in its own terms. Every side-dispute distracts from the priority of getting the people on the posters in the header image back to their homes (if they still stand) and families (if they still live).

Also last week, an open letter was published in the New York Review of Books. Signed by eminent scholars in the field of Holocaust and Genocide Studies, I did not agree with every word or emphasis. But the statement that “as academics, we have a duty to uphold the intellectual integrity of our profession and support others around the world in making sense of this moment” is inarguable. Holocaust education, if it is to be meaningful, must start from the facts. Murray and Roberts are both guilty of twisting facts to suit an agenda. It is not entirely clear what that agenda is, but I suspect Murray’s description of the Holocaust earlier this year as when Hitler “mucked up” should be considered when reading anything else he says on the subject.

This will not be easy, because those facts are uncomfortable. None of what follows is appropriate for school audiences, and it is challenging for adults. But as the historian Alex J. Kay wrote in his superb (and harrowing) Empire of Destruction it is important to remember that “…writing a sanitised version of these events would only succeed in making them appear more abstract; realism and accuracy would be sacrificed in favour of palatability. […] If this book is hard to read, let us for a moment imagine how difficult it must have been for the victims to suffer the events described here.” (Kay, Empire of Destruction, p.15)

In fact, it is only by hiding behind our sensibilities that Murray and Roberts can engage in what is, in my opinion, very close to outright Holocaust revisionism. It also suggests (by the by) that neither of these men have really confronted how terrible some of the crimes of the Holocaust actually were. Unfortunately, rebutting them requires that we do, however reluctantly. But first, what have they persuaded some people of?

Firstly, that the Nazis (if we allow, in the face of contemporary scholarship, that such a reductive defintion of the perpetrators is useful) were ashamed of their conduct. The “evidence” for this is the examples of psychosomatic reactions to violence (for example, stomach pain or vomiting) and the use of alcohol “to forget”. The psychosomatic point, incidentally, is useless. Disgust and bodily reactions are not correlated straightforwardly, and in any case do not seem to have actually incapacitated perpetrators in many cases. If they had caused the perpetrators to stop, that would be one thing. But they didn’t – they carried on.

From this starting point of a lack of shame, the following conclusions are drawn: the Nazis were ashamed, therefore they didn’t show enjoyment of what they were doing; therefore they did not publicise their crimes or worked to keep them secret; and therefore they covered up their crimes – though the possibility that erasing the traces of their actions had more to do with avoiding punishment once the war was lost is not really explored. On this basis, they reach the conclusion that “Hamas were worse than the Nazis” like two drunk men wondering why the whole bar is looking funny at their borrowed Nazi uniforms. Not that I am in any way suggesting that either of these men would do such a thing. The speed with which with one lawyer received a threat of libel action from Murray for terming his argument “Nazi apologia” suggests he may be sensitive to that.

It could be argued that this is a storm in a social media teacup. But that is to ignore the lasting damage done by glib comparison and badly thought-through allusion. Even if Murray or Roberts disputes my characterisation, it is certainly true that their words are being understood in this way.This was the basis for the castigation of Gary Lineker earlier this year, by the way, and I am deafened by the silence of some of those who shouted very loudly that the Holocaust could not be compared.

A final warning: the next section is very challenging. To minimise the trauma, I have mostly used the written word rather than images. I have also highlighted key parts of texts to minimise the need to linger. The texts are sourced and attributed to a number of volumes.

Source 1: Report from Major Rosler to Infantry General Schniewindt, January 1942 (Ernst Klee, Willi Dressen, and Volker Riess (trans. Deborah Burnstone), Those Were the Days: The Holocaust as Seen by the Perpetrators and Bystanders. London: Hamish Hamilton, 1993 (1991), p. 118.)

“The pit itself was filled with innumerable human bodies of all types, both male and female. It was hard to make out all the bodies clearly, so it was not possible to estimate how deep the pit was. Behind the piles of earth dug from it stood a squad of police under the command of a police officer. There were traces of blood on their uniforms. In a wide circle around the pit stood scores of soldiers from the troops detachments stationed there, some of them in bathing trunks, watching the proceedings. There were also an equal number of civilians, including women and children.”

This clearly challenges the idea that the Holocaust was not seen as entertainment. It clearly was: why else would people be standing around in bathing trunks? Why bring children?

Source 2: Witold Pilecki’s report from Auschwitz (Alex Kay, Empire of Destruction: A History of Nazi Mass Killing. Yale University Press, 2021. p. 217)

“The penal company was working in the square, transporting the gravel that was dug out of a pit. Apart from that, some commando was freezing while carrying out ‘exercises’. Next to the pit, three SS men […] came up with a game. They were making bets, with each one of them putting a banknote on a brick. Then they would bury a prisoner alive, upside down, covering his upper body in the pit. They would look at their watches, and time how long the prisoner kicked his legs up in the air. […] The one able to most accurately predict how much time a prisoner buried alive would kick his legs before he died – was the one who collected the money.”

Both Murray and Roberts suggest that the concentration camps and gas chambers were developed as a “civilised” alternative to mass shooting. But as we see here, the camps were the scene of killing as entertainment just as callous as anywhere else. We additionally need to recognise that the camps did not replace shooting: fully a third of the Holocaust’s victims were killed by bullets, among small and remote communities where the logistics of deportation were inefficient. These killings continued long into the war.

Source 3: Letter from SS Obersturmführer Karl Kretschmer to his family, October 1942 (Ernst Klee, Willi Dressen, and Volker Riess (trans. Deborah Burnstone), Those Were the Days: The Holocaust as Seen by the Perpetrators and Bystanders. London: Hamish Hamilton, 1993 (1991), p. 171)

“Since, as I already wrote to you, I consider the last Einsatz to be justified and indeed approve of the consequences it had, the phrase: “stupid thoughts” is not strictly accurate. Rather it is a weakness not to be able to stand the sight of dead people; the best way of overcoming it is to do it often. Then it becomes a habit. […] the more one thinks about the whole business the more one comes to the conclusion that it’s the only thing one can do to safeguard unconditionally the security of our people and our future.”

Kretschmer was writing to his whole family: he addressed his children by name and signed off “Your Papa”. He was clearly not ashamed of what he was doing but of his “weakness” in not enjoying it. But this did not stop him. As he sternly reminded his children, “the best way of overcoming it is to do it often. Then it becomes a habit.”

But then, not all children of perpetrators were kept far away from their fathers’ actions: these are the children of Auschwitz commandant Rudolf Hoess in the garden of their villa in the camp – about 200 yards from Crematorium and Gas Chamber I.

Source 4: the wife of a perpetrator recalls breakfast with her husband near the unit’s operations. (Christopher R. Browning, Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland. London: Penguin 2001 (1992), p.127)

“I was sitting at breakfast one morning with my husband in the garden of our lodgings when an ordinary policeman of my husband’s platoon came up to us, stood stiffly at attention, and declared, ‘Herr Leutnant, I have not yet had breakfast.’ When my husband looked at him quizzically, he declared further, ‘I have not yet killed any Jews.’”

Since this is a deposition from the 1950s in an investigation deciding whether or not the woman’s husband should be put on trial or not, one can assume that she was trying to put her husband in a positive light. But that doesn’t change the fact that she was having breakfast with him in this location: why, following Murray or Roberts, was her husband not ashamed of what he was doing? Why did he ask her to visit? There is neither shame nor secrecy in evidence. Indeed, one might speculate that treating her to accommodation and catering was a kind of, well, boasting.

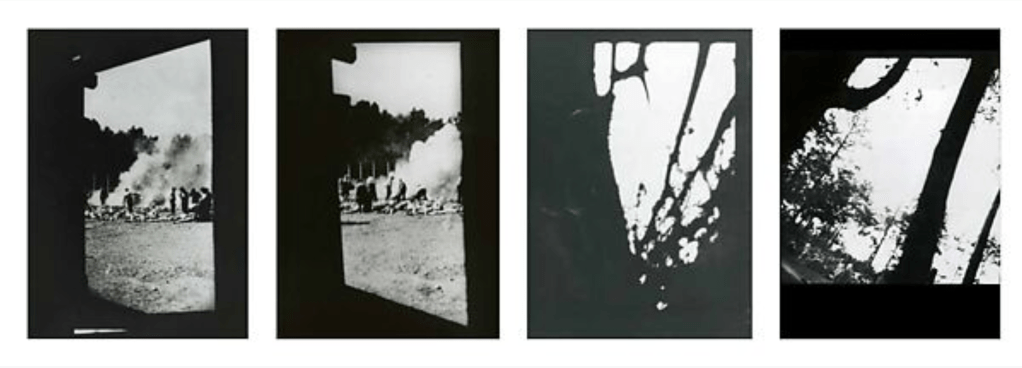

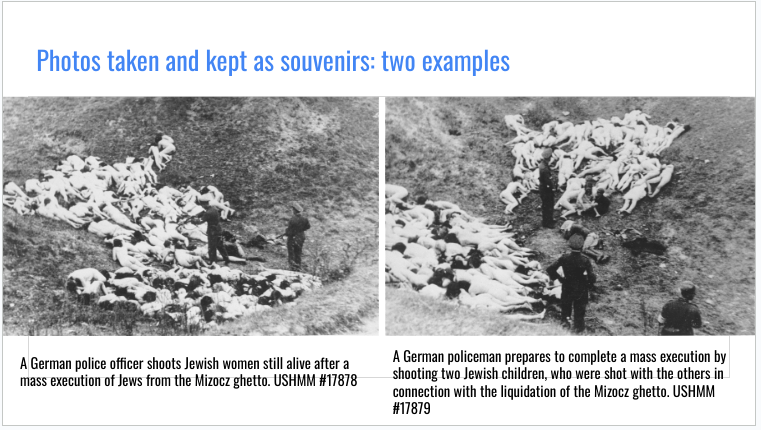

But what about the bodycams, asked one person on X, demonstrating that access to technology does not guarantee insight. Why didn’t they have bodycams? Well, it was the 1940s and they hadn’t been invented yet. But – as I pointed out in fact – the visual record of the Holocaust is mostly images taken by the perpetrators. Yes, theoretically there were restricted areas. But there were also tours of the Warsaw Ghetto which toured the site like a safari park. And many of those images are the ones around which we often frame commemoration. There is film footage of shootings. There are whole albums of photos taken and collected by the perpetrators. Including the images which follow, which are the hardest and most harrowing ones I can justify reproducing.

These images have no use. They do not do anything but allow the perpetrator to relive the moment. They came to light because they were given away by their creator after the war. He clearly felt no shame in having them nor did he fear retribution afterward. These are trophies, like jaded businessmen who shoot elephants for their “Kodak moment”, or men posing with drugged tigers on their dating profiles.

Finally, we have the issue of alcohol. It was certainly in plentiful supply in all parts of the Holocaust. It was a lubricant and a lowerer of inhibitions. But the diary of Johann Paul Kremer, one of the doctors who conducted “selections” of newly arrived prisoners wrote a diary (again, not concerned about discovery) full of references to drinking and dining.

Source 5: Dr. Johann Paul Kremer in Auschwitz (Ernst Klee, Willi Dressen, and Volker Riess (trans. Deborah Burnstone), Those Were the Days: The Holocaust as Seen by the Perpetrators and Bystanders. London: Hamish Hamilton, 1993 (1991), p. 261)

27 September 1942: Today, Sunday evening, 4-8 o’clock, Community House social evening with supper, free beer and tobacco. Speech from Commandant Hoess and musical, as well as theatrical presentations.

28 September 1942: Tonight attended eighth Sonderaktion. Hauptsturmführer Aumeier told me that Auschwitz concentration camp is 12km long, 8km wide and 22,000 [acres] in area. […]

Kremer does not seem to have drunk “to forget”, like some legionnaire in a black and white B-movie. He couldn’t forget – Kremer was running medical experiments and justaposes references to food and drink with “fixing” his “samples” of tissue. Conducting selections was a relatively bloodless part of his day. In a further blow to the “secrecy” claim, he wrote in November 1942: “Sent off a packet of soft soap (about 12 pounds) worth 300RM to Maria and Gretchen.” The goods of the murdered, when they weren’t furnishing the tables of their killers, were being sent to their families. How else did they get hold of the “wonderful-tasting Bulgarian red wine which put [Kremer] in a wonderful mood” the night before he left Auschwitz?

I have deliberately avoided reference to the atrocities of 7 October in this piece. There is no question that the attackers of Hamas committed horrendous and bloody crimes, which will no doubt continue to be documented. But one does not have to engage in this kind of comparison, which cheapens and debases both sides of the equation. The crimes of Hamas are the crimes of Hamas. One does not need to engage in a tawdry devaluing of previous crimes to do that. And one should be extremely suspicious of why Murray and Roberts have gone to such lengths to do so. All their disingenuous misreadings do is add fuel to a fire of outrage that needs no boosting.

With thanks to Dr Waitman Beorn of Northumbria University, whose comments on a version of this piece for another context emboldened me to make it public. All responsibility for any errors, of course, lies with the author.

Note: this piece was originally written and published in November 2023.