Tags

Barnes Wallis, Dambusters, Guy Gibson, icon, Lancaster, representation, Scampton, Spitfire, UKIP, World War 2

Seventy years ago last night, nineteen Lancaster bombers left RAF Scampton in Lincolnshire. 617 Squadron had been formed only a few weeks earlier, its mission a secret even from the pilots and crews. They had only been told of their objective – to break the dams of the Ruhr valley and thus disrupt German industry – earlier that day. The following morning, on 17 May, 1943, the surviving eleven crews returned – some all but crashing on the base perimeter – and a legend was born.

This is a story that will be told a lot today: the last few weeks have seen a wave of publications, supplements and television documentaries. BBC Radio 2 will spend the entire day commemorating the raid, its presenters broadcasting from Scampton and Biggin Hill before a concert in the evening. The trailers for this have been a regular feature on Radio 2, portraying the raid as a feat of courage and technical accomplishment: as Dan Snow puts it in an article for the BBC News website, a ‘combination of science, flying skill, grit and the obvious impact of the raids’. In short, the story as it has been told and retold since 1943, especially in the 1954 film starring Richard Todd (as Guy Gibson, the commander of the raid) and Michael Redgrave (as Barnes Wallis, the inventor of the bouncing bomb).

Like any operation by Bomber Command during World War 2, the Dambusters Raid has been the subject of intense debate, with no clear consensus on whether the raid achieved its short or long-term objectives. The authors of the official history of the Strategic Air Offensive, Sir Charles Webster and Noble Frankland (a veteran of Bomber Command and subsequently Director of the Imperial War Museum) dismissed the raid’s impact as overrated. And the civilian cost of the raid was huge: approximately 1650 people were killed in the towns and villages beneath the Möhne Dam. From their aircraft, the crews watched the impact of their breaching of the dam. Guy Gibson recounted:

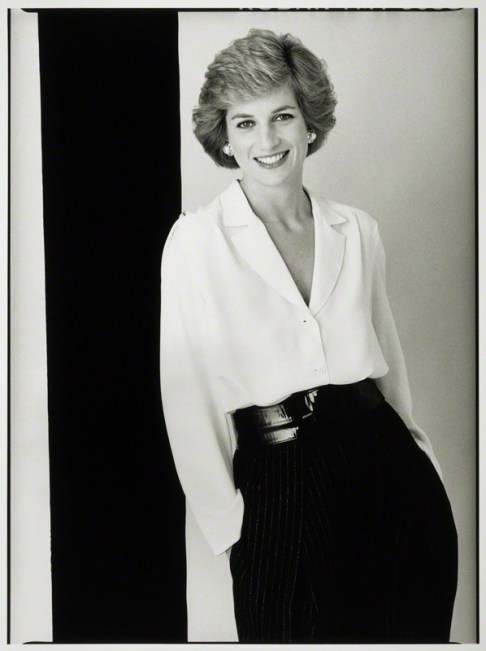

Guy Gibson (second from left) was 24 when he commanded the raid. He died in 1944 over Germany. IWM Photos.

It was the most amazing sight. The whole valley was beginning to fill with fog from the steam of the gushing water, and down in the foggy valley we saw cars speeding along the roads in front of this great wave of water, which was chasing them and going faster than they could ever hope to go. I saw their headlights burning and I saw water overtake them, wave by wave, and then the colour of the headlights underneath the water changing from light blue to green, from green to dark purple, until there was no longer anything except the water, bouncing down in great waves. The floods raced on, carrying with them as they went viaducts, railways, bridges and everything that stood in their path.

One survivor of the floods described what happened when the wave reached a labour camp where Ukrainian women were imprisoned.

Most were locked into their barracks and couldn’t get out. They were trapped inside the barracks as they were swept down until they came to the concrete bridge, where they were smashed to pieces. The terrible screams of the women trapped inside still rings in my ears.

Whatever the arguments about disruption of economic production – and Albert Speer made clear after the war that had the raid been exploited further it might have had serious consequences – the human cost was both immense and unavoidable. If the objective is to knock down a dam holding back millions of tons of water, the only way to do so without widespread and indiscriminate loss of life is to give a warning. Since the element of surprise was integral to the success of the operation, along with the necessity that water levels be at their highest, the civilian casualties have to be seen as at the very least an anticipated consequence of the mission. The moral questions about the raid mirror the broader questions around the Bomber Offensive, something which will certainly be revisited in the context of other forthcoming anniversaries, most notably (I suspect) that of the Dresden bombing in 1945. In that context, it is worth remembering as well that the Dams raid was codenamed Chastise.

In the meantime, though, a thought about the broader issues. In addition to the Dambusters and David Beckham, the news this week has focused on the progressive implosion of the Conservative Party over Europe, a process catalysed by the startling success of UKIP in the recent local elections. As entertaining as this is in terms of political theatre, I was struck by a tweet from Robert Eaglestone of Royal Holloway (@BobEaglestone if you’re on Twitter) who pointed out that ‘a problem with UKIP is that they believe the last thing to ‘happen’ in UK is WW2, so they create an odd ‘heritage’ politics.’ My response was this: surely the odd thing is that heritage politics are not perceived as strange?

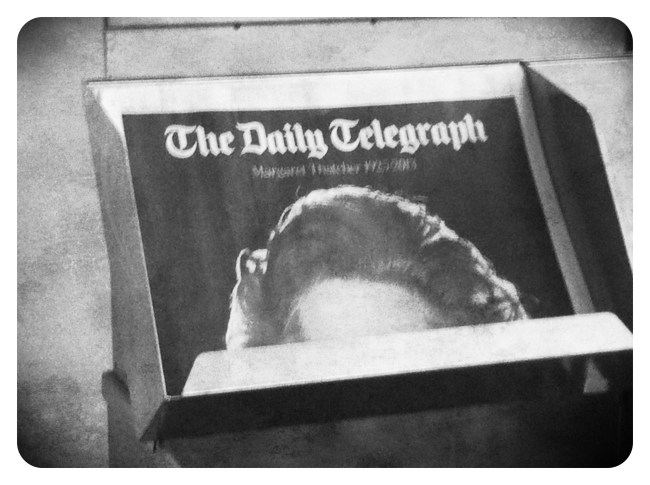

The air war of World War Two has a particular and peculiar hold over us. The Battle of Britain Memorial Flight is a standard part of our pageantry: witness the role of the iconic aircraft as part of the 2012 Jubilee and the 2011 Royal Wedding. Perhaps for the Jubilee it was comprehensible – the Queen is after all the last surviving head of state to serve in uniform during the conflict. But for the wedding of two people born almost forty years after the war it is curious. We are in a Barthesian mythology, where the constraints of the metalanguage in which we speak make the contingent and strange appear natural. To illustrate the strangeness, look at the photo at the top of this post, taken last week in a pub in Guildford. And ask yourself what would be the reaction if there were a German beer called Messerschmitt?

Quotations from the crews and witnesses taken from Max Arthur, Dambusters: A Landmark Oral History, Virgin Books, London 2009. ‘Friday Night is Music Night presents The Dambusters 70 Years On’ is on Radio 2 at 8pm.