Tags

Anne Frank, European Holocaust memory, Grabowski, Holocaust, Holocaust memory, Jewish Quarterly, Poland, Whitewash

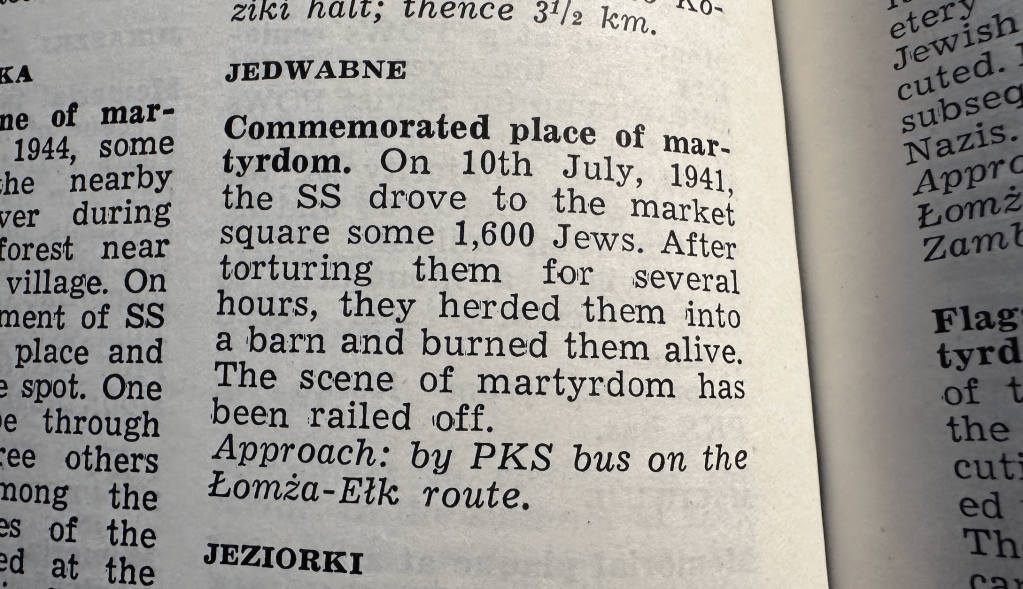

Above: Entry for the Polish town of Jedwabne in a 1968 Polish government tourist guidebook. Contemporary research has, in the face of current Polish government institutions, found that Jews were murdered by townspeople, with little (if any) involvement of the SS.

The Polish scholar Jan Grabowski has been treated with enormous disrespect and even cruelty by the Polish government and Polish society. The legal action in which he and Barbara Engelking were bound up in at the behest of a government-proxy thinktank/pressure group was unjust, persecutory, and ill-founded. The chilling effect this treatment may have on Polish academia in general, and Holocaust studies in particular, may be long-lasting. He has earned, many times over, the right to complain loudly about his treatment and warn against further abuses. Even if this were not the case, the depth and breadth of his research over decades would be reason enough to listen.

At the same time, his special issue of Jewish Quarterly, Whitewash, raises some questions. I hope Professor Grabowski will read this, and in the spirit in which it is intended; to get to the bottom not just of what happened, but why. For there is a gap in explanation as to why Poland, the recipient of huge resources for Holocaust education and commemoration since the early 1990s, should have gone down this route. My answer to this question structures my response.

Firstly, there is a strange gap in this publication where the years 1945-1990 should be. Many Polish voices, along with others in Central and Eastern Europe, have been vocal in arguing that it is time to treat this region beyond its postcommunist legacy. I couldn’t agree more on one level: the history of Poland did not begin in 1939, or 1945, and it will not end today. Jeszcze Polska nie zginęła/Kiedy my żyjemy (Poland has not perished as long as we still live). In discussing the legacy of the Holocaust, it seems slightly odd not to give more focused consideration to the social, political and ideological parameters within which memory developed. The 1968 anti-Jewish campaign appears, as do the pogroms in Rzeszów, Kraków, and Kielce. But the way in which the communist regime insisted on obscuring the identity of the victims as “citizens of occupied Europe” is important to understand, as are the links between Holocaust history and Polish history in general. Grabowski is right to complain about the arbitrary claim that three million non-Jewish Poles died, but he does not talk about the difficulties posed by those victims who were defined by the Nazis as Jews despite strong Polish and Catholic identities. The numbers are fuzzy in both directions, though the version Grabowski cites is certainly the stronger.

But the reader of the diaries by Adam Czerniaków (the Chairman of the Warsaw Ghetto) and the historian Emanuel Ringelblum will notice frequent references to the Christians of the ghetto, just as surely as readers of Lucy Dawidowicz’s The War Against the Jews will notice her invective against “apostates” and their role in the administration of ghettos. These were not homogenous and pre-existing communities trying to simply carry on the shtetl, but complex and heterogenous sites where people who often had little in common except their designation under Nazi ideology were forced to survive. In the camps, there were Jews who were “hidden” by assuming Polish identities, sometimes with the connivance of prisoner functionaries. Dividing a complex and interrelated past into two makes understanding the whole harder.

It is also important to explain to the casual reader that Polish nationalism evolved in a particular place and time. The messianic fervour of nineteenth century nationalism, asserting its particular suffering as a “Christ among nations” is an inheritance that cannot be ignored (especially in the Polish diaspora, where much older visions of Polishness have sometimes held sway). That the Polish answer to building national consciousness while enduring territorial dispossession resembles that of Jewish history is probably not a coincidence. It took a Polish Jew, Alfred Korzybski, to state succinctly that “the map is not the territory” in the 1930s. The Polish lament by Mickiewicz – “Lithuania, my country, thou art like health; how much thou shouldst be prized only he can learn who has lost thee. To-day thy beauty in all its splendour I see and describe, for I yearn for thee” – has a clear relationship to and resonance with the lament of Jeremiah:

If I forget thee, O Jerusalem, may my right hand forget its skill, [6] May my tongue cling to the roof of my mouth if I do not remember you, if I do not set Jerusalem above my highest joy. [7] Remember, O LORD, against the sons of Edom the day of Jerusalem’s fall, those who said: “Tear it down! (Psalm 137)

It is similarly significant that one particularly quixotic response to nineteenth century nationalism – the language of Esperanto – should be the invention of Ludwik Zamenhof (1859-1917) whose grave can be found in the Jewish cemetery in Warsaw. The street that bears his name was part of the Warsaw Ghetto. The predicament of being Polish and Jewish was an extremely complex one, informed by a very long history that Grabowski does not really explain. The leader of the Oneg Shabbat archive, Emanuel Ringelblum, was a product of both societies and cultures, though he died (and was betrayed) as a Jew. Other famous contributors to the archive also wrote in Polish. Henryka Łazowertówna (1909-1942) wrote her famous poem describing children struggling to survive, ‘The Little Smuggler’, in Polish, in which its relentless, searching rhythm can be truly understood:

Przez mury, przez dziury, przez warty

Przez druty, przez gruzy, przez płot

Zgłodniały, zuchwały, uparty

Przemykam, przebiegam jak kot. (Virtual Shtetl)

At Yad Vashem, and in many places besides, however, the source language is frequently omitted. There is a universal version in English, and a Hebrew text, but the source text does not appear – or at least it did not when I last looked. As James Young has written, all memory is local, but the complexity of locality needs to be fully understood.

This leads to the most sensitive part of my disagreement with Grabowski, that he has to some extent dismissed a legitimate narrative of Polish wartime suffering, as well as a submersion of the Polish experience in both communist-era and post-communist formations of memory.

To be clear, I agree that the “Righteous Defence” is overused, and that “Anti-polonism” is an accusation with a rather problematic theoretical basis. Grabowski’s point that the reasons why so few Poles (relative to population) engaged in rescue activity is both trenchant and important: “In Poland, during the war, hiding Jews was so dangerous precisely because there was no social permission to engage in it.” (p.84) If you’ve seen the residents of Jedwabne who did provide help to their friends and neighbours explain in Agnieszka Arnold’s film Sąsiedzi (2001) how they were ostracised after the war, this will come as no surprise.

As for the question of anti-Polonism, I have been in receipt of emails and messages from Poles with offended amour propre which have barely concealed their prejudice under indignation. I think many fellow researchers will understand this point without further argument. The use of the phrase “Polish death camps”, however, which in many ways is the fons et origio of this argument, is both factually inaccurate (they were not Polish-run or built on Polish advice) and insensitive to the fact that there are many Poles alive today whose ancestors endured the camps or who were killed by the occupier and collaborators. The Auschwitz tattoo, etched on the arms of those selected for forced labour in the camp, is a symbol of both Polish and Jewish suffering. That there is a much higher number of Jews who were so marked should not blind us to this.

The historian Alex Kay, in his pathbreaking Empire of Destruction (Yale, 2021) has identified seven campaigns of mass killing engaged in by the Nazi/German regime. He argues that his definition of mass killing (“the intentional killing of a significant number of the members of any group (as defined by the perpetrator) of non-combatants” p.4) is “less emotive, less politically contentious, and less dependent on specific legal interpretations” than the term genocide. As we have seen repeatedly (and continue to see) wrangling over the definition of genocide can prevent us from addressing the reality of mass killing. Genocide is a historical term which has been crowbarred into serving as a legal one, and for this reason is most useful after the fact – the least useful moment for victims.

Kay includes the murders of 100,000 members of the “Polish ruling classes and elites” and 185,000 civilians in Warsaw in his (empirical and conservative) tabulation of the number of victims of Nazi mass killing, which he puts at 12,885,000. As Kay, with David Stahel, has written, the focus on the murder of Jews has pushed the consideration of other kinds of criminality into the background. The challenge is twofold: firstly, to recognise that the massacre of European Jews was part of a “wider process of demographic reconstruction and racial purification pursued by the Nazi regime […] in each and every one of the territories occupied by German forces.” (Kay, p.3) But, secondly, we have to remember that the campaign against the Jews was the most completely realised and the second (after the disabled) to be put on a “systematic” basis. In short, the tragedy of the Jews deserves to be remembered as the priority for Nazi murderousness. As I often comment to students, 140,000 non-Jewish Poles were registered in Auschwitz, and half of them perished: in any other context, these are large numbers. That the Polish suffering is dwarfed by the huge preponderance of Jewish suffering should engender a certain humility in anyone who seeks to put them side by side.

There is a final aspect to the idea of legitimate grievance. The Nuremberg Tribunal of the “major perpetrators” began in November 1945, just six months after the end of WW2. Though it was inadequate, the indictment identified that “Since 1 September 1939, the persecution of the Jews was redoubled: millions of Jews from Germany and from the occupied Western Countries were sent to the Eastern Countries for extermination.” Simultaneously, on the insistence of the Soviet Union, the same indictment charged the that “In September 1941, 11,000 Polish officers who were prisoners of war were killed in the Katyn Forest near Smolensk” – though all present were aware that they had been killed by the NKVD, not the SS. Eighty years later, the present Russian government still insists that this was not a Russian crime, despite a guarded admission to the contrary in the 1990s. The struggle for Poles to talk sensibly about their past has been – and continues to be – difficult: it is not surprising (though not excusable) that Polish antisemitism in this era should be difficult to frame. The Russian position is gaslighting of an order comparable to the triumphant British claim to have “abolished slavery”, rather than having cashed out a failing concern in human suffering to the benefit of its perpetrators.

Finally, there is the issue of context. Grabowski talks about other nations which experienced Nazi occupation briefly and in passing. This is understandable, since the essay’s focus is on Poland and the Jews. Grabowski describes the Polish reaction to remarks by James Comey in 2015 when he observed that “In their minds, the murderers and accomplices of Germany, and Poland, and Hungary, and so many, many other places didn’t do something evil.” Grabowski’s commentary on the response by Polish museums notes that “Comey could have extended the list of culprits further, adding to it the French, Belgians, Dutch, Ukrainians, Belorussians and Balts” and that nothing was taken away from the validity of the argument by their absence. I accept this, but it needs to be pointed out that Comey didn’t: because the nations of western Europe are generally understood as helpless victims or Résistants, while the nations in the east are dismissed as primitive, bloodthirsty, and antisemitic. That I know many people in Poland who have spent considerable time and energy teaching their fellow countrymen the facts perhaps colours my response: this is not, and has not been, easy. Nor will it be in the future.

But the past is never simple, however we might wish otherwise. A few weeks ago, the violence surrounding the football match between Ajax and Maccabi Tel Aviv had many commentators making earnest noises about “the city of Anne Frank”, as though an offence to the memory of her diary were the ultimate transgression.

But Amsterdam was the city of Anne Frank in a very complex way. She was forced into hiding by German occupation and then helped by a group which was bound together by allegiance to the family rather than national ideals. Miep Gies, the primary individual remembered in this context, was born in Austria. If this was the city where the Franks hid it was also the city where they were betrayed, arrested, and deported – like a third of Jews in hiding in the Netherlands. There were 325,000 Dutch citizens in hiding, just 25,000 of them were Jews: the majority were evading recruitment for forced labour, and historians see the real crystallisation of the Dutch resistance around forced labour, not the Holocaust. Jewish deaths in the Holocaust comprise 40% of all Dutch loss of life in WW2. And accounts from those rescued often put their rescuers in a very critical light, with attempts at conversion, as well as exploitation and abuse, commonplace. Andre Stein interviewed many Dutch rescuers living in Canada in the 1980s in his book Quiet Heroes (1988), and found that social pressure on those who rescued was very hard to manage. Dienke Hondius and Conny Kristel have described the appalling ways in which returning Jews were deceived and abused on their return, leading many to leave by the 1950s. And Dutch claims of ignorance or misunderstanding of events during the war are powerfully challenged by Anne Frank herself, who wrote on 9 October 1942 that “We assume that most of them are being murdered. The English radio says they’re being gassed.” The resistance veterans’ celebration of the Radio Oranje call sign in The World at War sits (retrospectively) uncomfortably with their equivocation about what they knew: were they not listening to the same broadcasts as Anne? The Dutch historian Bart van den Boom has tried to shift the goalposts toward “subjective certainty” being required before Dutch citizens could be expected to act, in a manner that is as archly problematic as the efforts of many Polish historians and pressure groups.

Grabowski is of course right: nothing Comey said is changed or invalidated by his not mentioning the Dutch experience. But as social scientists and historians we can also acknowledge that it is significant that he did not mention them, while bracketing Poland and Hungary with the Germans as shorthand. Europe has dealt very incompletely with wartime collaboration, particularly as it concerns the persecution of the Jews. To an extent, Poland has carried the can for other nations with histories just as questionable or damming, and that is an important site of future research. It would be another whitewash for that not to be the case, in fact.

As I said at the beginning of this piece, Jan Grabowski is a superb scholar who has been treated very unjustly for trying to tell the truth – however complex and challenging it may be. He has done so at significant personal cost, and he deserves our admiration and our thanks for sticking to his insistence that academic research cannot be challenged on the grounds of sentiment or offended pride. I hope tonight, in his lecture in London, to hear a fuller account of his thinking.